n the tunnel in five, Joe,” his manager said, words that hit him in the gut more than the blows to come. He wrapped his hands again and unwrapped them again. Not for luck. Luck was something for people who still had a hope. Maybe today he’d make it a few rounds. Maybe he’d go down in the first. He was tired. He could use a nap. Or a coma. He couldn’t remember winning, but it happened. Once. The first. He was never much good with the hook, but that day in Bousillé-Bèze he took Halimi down with one punch. Of course he was as good as retired by then, half-blind, but no matter. Those were the days. He was making a name for himself. Joël L’incassable. Unbreakable. Even when he lost, the crowd was on his side. In Paris, they rushed the ring and tried to tear the judges apart. The publicity got him all the way to the States for a title match. But a good shot to his jaw took him down a second time. Something broke. And when he healed up it stayed broke. And he stayed on, broke and broken in Brooklyn. The first few losses hurt, because he tried. The next ten or so were pillowed with bills. After that, he lost count. Sometimes he tried, sometimes he took the fall, sometimes he didn’t know which he was, on or off. He’d flutter between punches like a film reel. Jab. On. Hook. Off. He let the wrapping alone and pulled the gloves on. He put on the robe. The colours had run and he couldn’t afford a new one. He looked down the hall. The lights of the stadium. He didn’t even know who he’d be losing to. He walked. It was that one win that stung. It never changed. 1-99 or 1-999 it was still there, weaving and dancing just out of reach. It would be easier to be zero. Vanquished. The crowd wasn’t roaring. This wasn’t the kind of place that roared. It mumbled. When he lost, they’d shout names. They’d throw croissants at him. They didn’t look anything like the ones back home. Just soggy supermarket pastry. But they still hurt. They still found things to break.

0 Comments

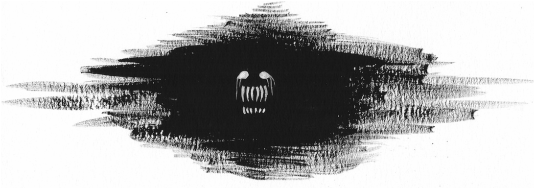

ix months living second to second, hoarding weekly allowances, shouldering extra chores like Atlas, scavenging for bottles in the greenbelt until the sun bursts like an ostrich egg on the hills and the hound up the street bellows him home to dinner. Day after day, week after week for six months of hard labour, time and pennies funneling down into a treasure trove he packs into a plastic bag from Mr. Grocer and ducks by his parents screaming to hop a bus striped orange like a creamsicle, heart cracking ribs with each pothole, in through the doors of Consumers Distributing, up to the counter, standing on tiptoes to jab a finger at page one forty-six of the catalogue, the clerk nodding like a priest at Vespers, disappearing through a passageway, returning an eternity of seconds later with a cardboard rectangle, money swapped, treasure for treasure, then the long ride home, the box cradled like a baby on his lap, deciphering the hieroglyphs, secret words and hidden meanings, this crossing only a psychopomp could love, finally home, past his parents howling, up the stairs, to dump the cardboard on the rainbow shag carpet, cutting the tape with a box cutter like he’s defusing a bomb, and out it comes in a rainfall of foam and plastic, the sum of fifteen million seven hundred and sixty-eight thousand grains of sand rattling and piling and crumbling through the hourglass. Him, here, now. Black and grey rubber. Four fingers and a thumb. A glove. It slides on easy. Made for him. Crafted and tempered in some factory in the far east. He plugs it into the grey slab and hits the power stub. He makes a fist, strikes a pose, like in the advertisements plastered all over his walls. His parents shriek like the Furies downstairs. He plays with power. For two minutes. Stretching into five. Reaching for six. Then, he takes the glove off, drops it on the bed. Disappointment wells up inside him like blood. Half a year gone, and his parents will roar straight on to Christmas.  he hits the horn again, aimed at no one in particular, knowing it will have no effect except to make the world around her just a little bit worse. Here she is, trapped in gridlock with no end in sight. For most people, it’s an inconvenience. Just another necessary evil in a long bastard of a day. For her, it’s life or death. This is the way she feels about everything, all day long. Somehow she keeps on living. This time, though, she could lose her job. She looks at the clock. Seven minutes left. If she gets there late, at best they’ll take it out of her pay. Again. She puts her hand on the lid of the cardboard box in the passenger seat. Lukewarm and fading. And there goes her tip, too. The right lane opens up and she makes her move, hitting the gas and swerving in front of a rusty old Civic. She flashes the finger in the rearview before the other driver can honk. Her lane is wide open ahead. She’ll show them thirty minutes or less. She crushes the pedal, flashing by all the gawking commuters on her left. Then she sees a flash of orange dead ahead and realizes why the lane was so open in the first place. She waits until the last minute and then screeches to a stop. The sound shocks the driver of the hatchback on her left enough that she can jam herself in front before he can do anything about it. A green sign above, like a beacon on a rocky coast, tells her the exit is just another hundred metres or so. Four minutes left, time for extraordinary measures. She swerves left into the carpool lane, accepting honks from all comers. They don’t know she has a passenger. Twelve slices of cheese and pepperoni. Cheese already stiffening in rigor mortis as it cools. She jumps ahead a few more car lengths and then hops right, then left, right again, more honking, screeching tires, brushing bumpers, windows rolling, new curse words birthed, and then there she is—running up the ramp to freedom. All that mess left behind her for someone else to deal with. Two minutes left. Just enough time. To make the right on Broadview, make the left onto Victor, make it to fifty-four just in time. She pulls through the stop sign without looking and something crashes onto the hood of her car, windshield spidering with cracks. She jams on the brakes, but whatever she’s hit grabs a hold of the wipers to keep from falling off. A man. A man in red spandex, mask over his eyes and rabbit ears. He’s pressed against the remains of the windshield, staring at her, cross-eyed, with a grin like an escaped mental patient. She looks at the clock. She’s going to be late. It can’t be avoided. All she can do is feel annoyed.  e had to fight, they said. When he asked why, they simpered and wrung their hands. No damsel to be saved, no kingdom to conquer, no villain to overcome. There was certainly no reward. But haven’t you always wanted to be a hero, they said. No, he hadn’t. He was moderately content with his mid-level salary, midtown condo, middling midlife mediocrity. They simpered some more. But what about flying, they said, bet you always wanted to fly. No, he said. Flying made him sick. In the end, they drugged him and stuffed him in a trunk. The next thing he knew, here he was, sitting on an ostrich on a ledge over a pool of lava. And they’d taken all his quarters. Bridle, reins, saddle. Just like a horse, they said. But he’d never ridden a horse. No problem, they said, this one flies itself. But ostriches can’t fly, he said. Shut up, they explained. He dug his heels into the ostrich’s side. Giddy up. It turned its head and hissed at him. He heard flapping above him, and looked up to see large birds circling. Buzzards. They didn’t look friendly. He peered down. Far below the ledge, the lava was rising. He didn’t like this. It was all too exciting. He liked monotony. He liked doing the same thing over and over. That’s why he’d answered the ad in the first place. Wave after wave, they told him, wave after wave after wave. Something hit the ledge near him with a wet slap. Steaming and stinking. Buzzard shit. The ostrich spooked and started to run for the edge. It spread its stunted wings. He was still pretty sure ostriches couldn’t fly.  hat a dive, he thought, wiping the sweat from his eyes and looking up at the old house. The peeling paint, the boarded front door. If it wasn’t on his route, he’d never bother coming all the way out here. It was the kind of place you’d expect to find slavering jaws and sinister lurking presences. He shoved another leaflet in the mailbox and headed off on his way, back across the open field west of the white house. Several feet away and one storey up, he lurked in the dark bosom of the attic, waiting. He couldn’t go downstairs because of the light, so he lurked here among the dust and useless things that pile up attic corners. If some wannabe adventurer came stumbling along, without a light, he would eat it. Other than that, there wasn’t a whole lot to do except continue lurking. An adventurer was stringy business, all muscle. And they were always carrying things—gems and swords—junk that irritated his already irritable bowels. Sometimes he got a Jehovah’s Witness, but they always talked too much. And the Avon ladies gave him gas. He hoped if something showed up, it would at least have the common sense to be carrying a brass lantern. Maybe then he could get a good look at himself. Having lurked in a dark place his whole life, like his parents before him, he had no concept of his own appearance. He felt out of shape. Lurking was not good exercise. And he was suffering from chronic Vitamin D deficiency. His mom told him he was beautiful, but what else could you expect from your mother. He could be disgusting, hideous. How would he even recognize the difference? He had nothing but darkness to measure himself against. And darkness wasn’t anything but a place to lurk. He could take a chance. Throw open the windows. Head out into the world with all its sunshine and possibilities. But he’d have to put some pants on first. And there was his photophobia to worry about. His stomach growled. The whole thing was rather depressing. In the end it just seemed like so much fuss. It was easier to stay here. To lurk a while longer, and wait for something to happen to him instead. Even if it never did.  very time, he has the same question: what year? Enough with the 20XX bullshit, just tell me the year. It’s true, the defrost left him crabby and constipated. The Doc is looking old. A little less hair on top, the white in his beard whiter than ever, almost translucent. Like he was slowly fading away. They don’t bother to make small talk. He’s been in suspended animation, dreamless, and the Doc’s been buried in research and planning. They live to thwart, that is all. The year actually doesn’t even matter anymore. What is more important is the time. The iteration. How many times have they done this already? Nine? Ten? More. More than could ever be necessary. They spend some of that time going over his rust spots with steel wool and blue paint. The Doc doesn’t even bother with new gadgets anymore. Why fix it, if it ain’t broke. Just let it break. Let it stop. Eight more robot masters to fight. Whichever order you’d like. At first it was a novelty, now it’s a chore. The designs, the names, it’s all just a rehash now, like even their adversary is tired of the game. And who would it be this time? Some mysterious ‘other’ Doctor. Great. Do they really need the theatrics? No matter who is prancing about as the bad guy this time, however complex the back-story they’ve been sent, you always know it’s going to be him in the end. He might put on some sunglasses or dye his moustache, but when the curtains come down it’s always him. The Doc snaps the blaster on to his stump and yawns. He’d yawn too, if he were only human. They’d do it again, only to do it again. Sisyphus had it easy. Maybe this time, when it’s over, the freeze will last longer. Maybe forever. Maybe this time, he’ll finally get some rest. |

8bitmythsRemember when you were a minipop, and you saw that film, you know, the one you loved that never had a sequel? Well, let's say it did. And it was just like you imagined it, only a little bit worse.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed