e comes alone now. He arrives early in his brown three-piece tweed, in through the revolving doors squeaking like a mischief of mice. He pats at his white laurel of hair and moustache, but nothing can tame them now. He can’t work the automated teller and he always buys his ticket with change, counts it out to the penny, even though they don’t take those anymore. He doesn’t tip the greasy concession kid, whose pimples are the distant ancestors of the colony of acne that has lurked in the concession stand for generations. He takes the stairs one at a time, holding on to the brass banister with all the might left in him. He’s Sir Edmund Hillary making his final ascent, but there is no ticket-taker to greet him at the summit, no torch-bearing Sherpa to usher him to his seat. He’s on his own. He follows in the footsteps of others, etched into the carpet through years of pilgrimages to see opera singers, magicians, monologists and burlesque dancers. He stands at the top of the stairs to catch his breath. He feels the concrete blooming through the threadbare carpet. There’s no one to nag him on. He pushes through a veil of mothball and velvet and emerges onto the balcony. He settles into his seat with grunts and groans like an old house in winter. The springs are busted and the fabric torn. The chair beside him sits empty. He can barely see over the gold filigree edge. The theatre below is empty, except for a man snoozing in the front row and a pair of teenagers necking and fondling near the back. The stage has been surgically removed, a white screen stretched across where it used to be like a death shroud. They lobotomized the place and turned it into a picture house. He looks down, but he can’t read his ticket no matter how close he brings it to his face. He doesn’t know why he comes here or what he’s here to see. Something loud. Something to fill in two hours of his day, like the first snow on darkened street. And when the thing’s over he’ll still be here. Still alone. No one will hear his complaints. Just an empty chair next to him, empty on the cab ride home, empty at the dinner table. A cavalcade of barren chairs parading past him. Left to wither like a joke without the punch line.

0 Comments

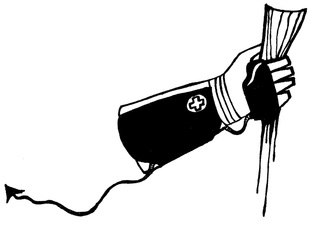

ating disorder, the vet says. Legs up on the desk, hands behind her head. Real common, you could try it on a different food. Tried that, doc. You could try switching up mealtimes, she says picking her teeth. Feed it at night instead of mornings. Can’t do that, doc. Early riser, eh? Happens to men as they get older. It’s not that. I can’t sleep a damn anyway. But I got to keep him on a schedule. Okay then, she says spreading her hands on the desk in surrender. You could take it to a psychologist. They have those for pets now, you know. Cost you a fortune. No thanks, he stands in the doorway. Say, doc, what do you call those animals that don’t reproduce. Like the normal way. She leans forward, What kind of animal you say this was again? Exotic. He tips his ballcap, Thanks, doc. Parthenogenesis, she says as the door swings closed. He does the rounds, emptying the dehumidifiers in each room and setting them to high. It was a hot one outside, these early days of summer. But you’d never know it in here. There’s a certain kind of smell that the black garbage bags taped to the windows give off as they cook in the sun. In the kitchen, he checks the clock on the stove, an old habit, as he dumps some kibble into the red plastic bowl and heads up to the attic. Over the years his eyes have adjusted to the dark. He finds the door to the cage and opens it. At the back he can just make out the wet circles of its eyes. Come on, buddy, he says, You got to eat. It crawls forward, gives the food a sniff and then pushes the bowl away. Its hair has come out in patches, and now it looks like a pink little ragdoll. Its ears droop like butterfly wings. Don’t look at me like that, he says, It’s not my fault. He stomps back downstairs with the bowl. Dumps it in the trash. But maybe it is his fault. He’s broken all the rules. There were just so many. Don’t do this, don’t do that. When you look too hard at any of it you go cross-eyed. He hears something upstairs. A song? No. The house has been silent for years. It didn’t sing to him anymore. Not because of the rules, at all. He knows the truth. It was just lonely. He starts to cook. Chicken drumsticks, the way his mom used to do them. He watches the clock on the stove crawl toward midnight. They were both just so lonely.  irch and bird call, mossy green, rocky stream and escarpment. If the hike had a soundtrack it would be the twang, twang of a jaw harp. It is the kind of day that he would call perfect. If he weren’t perfectly lost. It started with the goat shit back in the pasture. An omen he tried to wash off in the old swimming hole, but the brown froth there stank worse than the shit. He sits on a boulder here, dumps his rucksack and drains the last of his water bottle. He knows these woods like the back of his hand. Knew them, once. But his hands are looking less familiar every day, too. Wrinkled, hair silvering down the wrist. Yahoos on ATVs have wrecked the old trails and a fire ran through at some point. Probably lit by the same yahoos at some Pabst infused campsite. He scans the trees. Nothing looks the way he remembers. He can’t find it. Something itches at his palm and he turns it over. A stripe of orange. Furred and shivering in a slow procession across his skin. Caterpillar. He reaches out to pet it. The fur soft against his fingertip, feeling this instant of connection. This tie to mother nature. We’re all one, he thinks. His finger there on the single spine like a tuning fork. He feels at peace. Then he feels pain. A lot of it. Hornet sting pain. Root canal pain. Miniature hydrogen bomb pain. He knocks the caterpillar off and pinwheels back, falling onto a soft green cushion. Poison ivy, he thinks. Giant hogweed. It starts to rain. But it’s there, from his prone position, he spots it. Pushing back tamarack and vine to uncover it. The log. Running back into dense wood, rock and darkness. He puts his head into the opening. He can barely make out the pinhole of light at the other end. The sweet sick smell of decay. He eases in. It’s tighter than he remembers it. Shrinking, like people do as they age. Or maybe he’s let himself go. He has to tuck his arms in at his sides, stretch his legs out straight. He wriggles forward. The slime on the inside of the log helps him. It’s maybe eight feet to the eye of light, opening wider ahead of him. Just a little farther. A little more. Why didn’t he exercise more? Why did he eat so much? A little more. The smell is oppressive. Marching up his nostrils. Not decay, death. He tries to move his arm, but they’re both pinned now, his head jammed against the roof. Stuck. So close. Nobody knows he’s here. They wouldn’t find him for days. Years, even. He panics. His body convulsing. His head pops through a membrane of cobweb and he tastes fresh air. Sunlight. His arms are still trapped but he can move his head. The secret glade. His place. Like a time capsule. There, under the rocky shelf, right where he left it, his guitar in its case. Probably perfectly in tune, too. Tweet tweet a bird says above him. I’m not lost anymore, he whistles back. It may have started with shit, but he won’t let that be the word of the day. Something hits him in the back of the head. Flap flap of wings and caw caw overhead. The something runs down his neck and drip drips onto the rock below. But he doesn’t squirm. He doesn’t fight. If he just doesn’t move things can still be perfect.  ix months living second to second, hoarding weekly allowances, shouldering extra chores like Atlas, scavenging for bottles in the greenbelt until the sun bursts like an ostrich egg on the hills and the hound up the street bellows him home to dinner. Day after day, week after week for six months of hard labour, time and pennies funneling down into a treasure trove he packs into a plastic bag from Mr. Grocer and ducks by his parents screaming to hop a bus striped orange like a creamsicle, heart cracking ribs with each pothole, in through the doors of Consumers Distributing, up to the counter, standing on tiptoes to jab a finger at page one forty-six of the catalogue, the clerk nodding like a priest at Vespers, disappearing through a passageway, returning an eternity of seconds later with a cardboard rectangle, money swapped, treasure for treasure, then the long ride home, the box cradled like a baby on his lap, deciphering the hieroglyphs, secret words and hidden meanings, this crossing only a psychopomp could love, finally home, past his parents howling, up the stairs, to dump the cardboard on the rainbow shag carpet, cutting the tape with a box cutter like he’s defusing a bomb, and out it comes in a rainfall of foam and plastic, the sum of fifteen million seven hundred and sixty-eight thousand grains of sand rattling and piling and crumbling through the hourglass. Him, here, now. Black and grey rubber. Four fingers and a thumb. A glove. It slides on easy. Made for him. Crafted and tempered in some factory in the far east. He plugs it into the grey slab and hits the power stub. He makes a fist, strikes a pose, like in the advertisements plastered all over his walls. His parents shriek like the Furies downstairs. He plays with power. For two minutes. Stretching into five. Reaching for six. Then, he takes the glove off, drops it on the bed. Disappointment wells up inside him like blood. Half a year gone, and his parents will roar straight on to Christmas. |

8bitmythsRemember when you were a minipop, and you saw that film, you know, the one you loved that never had a sequel? Well, let's say it did. And it was just like you imagined it, only a little bit worse.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed