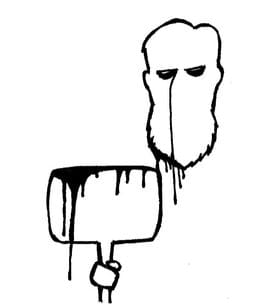

e grabbed the shovel from behind the garage and limped down the drive. He kept his back to the house, crouched there darkly in the snow. But he could feel the crack in the drapes. His mother’s eyes on him. They never left him alone. Not ever again. They worried, as people do. He was the youngest, after all. He needed special attention. They pulled him out of school and did his lessons at home. His father sold the firm and started a small consulting business on the side. His parents took turns going for groceries. He was never out of sight for long. If he sneezed, they’d put him to bed, feed him comic books and flattened ginger ale. Pile hot water bottles around him like sandbags. His brothers and sisters grew up, as people do. They left home, marching one by one. He was allowed to wave them off in the driveway, mother on one side and father on the other, hands latched to his shoulders. Around the corner they went, at the end of Lincoln Boulevard and on into their real lives. Some of them came back for summer vacations for a while. Now they were only a family occasionally, the way a rock skips across the dawn surface of a lake. Skip, a wedding. Skip, a baby shower. Skip, Christmas. Skip. This was the first year no one had come home. They never would again. Not in the same way. They sent Christmas cards instead from their own homes. The shovel scraped across the asphalt. They let him go this far, to the end of the drive. There was a timer going, back in the house. His mother had drawn up elaborate algorithms calculated to negative temperature and hypothermic probabilities. Winter was his favourite time. The snow dragging the trees down low to meet each other up and down the boulevard. The day dying fast behind the big hunched houses. He snapped his fingers. Wink, went the lights at 542 at the end of the street. Snap. On came 577. Snap, 602, closer. Snap, 613, closer still. He conducted comings and goings on the street. With the last layer of frost shaved from the drive, he pulled the aluminum trashcan out from beside the fence and began the salting, crisscrossing back and forth. The shovel had been given to him by his neighbour, when his granddaughter bought him a snowblower. It was a metal one, the kind they didn’t make anymore, with an edge like an ice skate. He remembered the stories about the old man, dead now many years back. He hacked his family into pieces with the shovel. Or so they said. Things seemed so much simpler back then. When he was done the asphalt glowed. It was like snow hadn’t even been invented yet. He snapped his fingers. The lights came on next door. He leaned on the shovel at the end of the drive. His toes edged up to the sidewalk. His back hurt. Most things hurt these days. He’d grown a beard. A long one. And at some point it had gone grey. He’d grown old, as people do. He turned back to the house, just as it flared up like all the Christmasses of his life. The lights were strung in the trees. The burnt strands loomed high, where the branches had carried them to die. He clomped up the drive, dragging the shovel behind him. The metal made a sound like a fork across a dinner plate. Somewhere in there his parents were wrapping the very last of the presents. They took care of him, as people do. Really good care. One day, it would be his turn.

0 Comments

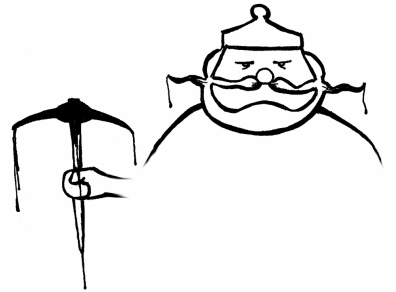

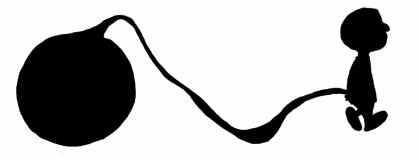

rom the tower, he watches their approach. Two meaningless black specks. He’s been alone for so long. Nothing but the echoes of ghosts to keep him company. He reaches down inside, blindly fumbling around the pit of his stomach. And there it is. Still, after all these years. A hot marble. Anger. It rises from his belly, like bile or hot coals, rattling up his ribcage, clawing up his throat, filling his mouth, his nasal passages, running through his antlers like an electrical current, and finally, boiling down into his nose. They walk. They walk some more. They walk and walk and walk. And they stop. “How far have we come?” asks the Dentist. “A ways,” answers the Prospector. “How far to go?” “A ways away.” And then they stop stopping to walk. And they walk some more. As they walk, they sink. Deeper with each step. The temperature is rising, vapour wafting off the snow, clinging to them in grey strands. It’s like pressing through television static. They sink and the snow begins to tower over them on either side, slush sucking at their feet. A red light burns through the mist ahead of them. The air clears, pulling back like curtains to show walls and gabled roofs, gaping windows, a turret with a red light glowing in its window. A castle cut from the ice. It had been magnificent, full of colour and light. Now, streams of water run down the eaves, as the whole thing sinks. The two travelers stands in its shadow. High above them, the red light in the turret goes out. They climb the stairs. The Dentist can’t reach the knocker, so his old friend boosts him, grunting with the effort. “You got fat.” “You got old.” “Doesn’t everything.” Boom, boom, boom. The sound echoes through the structure. It takes minutes to fade, but no one comes. The Prospector leans against the doors, and they swing inwards, drooping on their hinges. As they enter the yawning halls, there’s the whiff of gingerbread and nutmeg. Then the rush of mold underneath. Tinkers and tailors, whittlers and cobblers: the place should be a buzzing hive as the crafters make the last push before the big day. But the workbenches sit empty, stools overturned. Holly and ivy hang like corpses from the rafters. Their footsteps echo, the Prospector loping and the Dentist scurrying to keep up. They pass one hall after the other, a straight line like a throat, heading deeper and deeper toward the belly of the place. They finally reach the end. A little light from the window hits a chair in the centre of the room. A throne. Built from antlers. The Dentist counts: One, two, three… A red glow lights up the rest of the scene. The Dentist sees more: Four, five, six, seven… The Reindeer is seated on the throne. Sprawled unnaturally, like a man. His nose glows red. A darker, more crimson red than they remember. Eight, the Dentist finishes. Eight pairs of antlers. The Reindeer slides from the throne and finds his hooves. The shreds of a blue vest hangs from his shoulders: the remnants of the Walmart takeover. He paces a wide circle around the others, as they spread out to meet him. The Prospector spins his pickaxe, the metal glinting in the half-light. The Reindeer paws the ground and snorts. The Dentist tries to remember anything from the Brazilian jujitsu class he took last year in Tarzana. Everything goes still and silent like a thread pulled tight. The Reindeer’s nose glows brighter than ever. A supernova. It lights up all their faces. The lines and scars. They’re not friends anymore, thinks the Dentist. Friends are people who spend time together. Who know each other. Who can hurt you the most, but don’t. But these are not my enemies, thinks the Reindeer. Their only enemy is time. The time that was stolen. The time they’ve wasted. Another year, thinks the Prospector. Another year almost gone. The red light in the room fades. The Reindeer’s nose dies out to black and he drops his head. The Prospector lets his pickaxe fall to the floor. The Dentist relaxes his stance. “I want to go back,” he says. But no one is listening. The others sit on the floor, dejected. The Dentist reaches into his parka and brings out the wad of papers. He crumples them up and lights them with a pack of matches. The flames curl the ends of the paper: “Agreement for the sale of Christmas T…” The final word already burned away. As he searches for scraps of wood to pile on top, his foot hits something. He leans down and picks up a wooden soldier. Only half-carved. He finds his scalpel and gets to whittling. It comes out cleanly and quickly from the wood. Old habits. He makes the lines softer and cuts out the rifle. “What’re you doing?” The Prospector leans over him. “Making a gift.” He carves a smile onto the face. Something kind. “For who?” He doesn’t answer, because he doesn’t know yet. There are other wooden blocks scattered across the floor. So much left to carve. The Prospector goes to the cupboard and pulls out the old things. He gets dressed. Fur pants and suspenders, red wool and wooden buttons. He sits on the throne to pull on the black boots. The Reindeer returns, dragging the sleigh out of storage. The Prospector eases him into the harness, gently placing the bridle between his teeth. The Dentist runs his hand along the tarnished brass rail where the reins are still looped. The oak boards have been eaten by rot and worms. It would fall apart, tomorrow or next year. But for now it would hold together.  he roar of the rotor fills him, like the slow, sick revolution of his soul. His body’s numb. Not from the cold but from skipping across the world like a small stone. Skip from west coast to east, skip over the Atlantic to London, skip on to Oslo, skip to Svalbard, skip skip skipping nowhere, to the very edge of the map. He rubs the frost from the window and peers down. Water and ice and something else: the dark hulking forms of the rigs anchored off the coast. He’d left a heatwave in L.A. and already heat was part of his past, like innocence and good cheer. For the past three days, they’ve been stuck at the ice station waiting for the storm to clear, crouched by the radio, drinking schnapps and eating from cold cans of spaghettios. This morning he’d been ripped from his tent by the pilot and stuffed in the helicopter, both of them still drunk from the night before. The pilot shouts something at him in Norwegian. Too much to hope for a crash: sudden heat and fiery end. The helicopter descends toward a bald white expanse. Below a figure waves them down. He feels inside his parka to make sure the papers are still there. Four sheets versus several thousand miles. The pilot is shouting at him again. He doesn’t understand. He doesn’t understand anything. But as he leans closer, the pilot reaches past him, swinging the door open and shoving him hard into empty space. It’s maybe eight feet, but it feels like Alice’s rabbit hole. Tumbling through cold, smelling cold, tasting it, the cold sinking into his pores, down into his soul. He never thought he’d come back. But here he is. He opens his eyes to see the Prospector towering over him. Hs fiery beard and moustache so white with age, or frost, he almost looks like his old boss. He opens his mouth to say something but the wind is howling, the storm closing in again with shards of ice blowing in from the sea. The Prospector pulls him to his feet and they stumble toward a mound of snow. A dark hole is cut into it. A cave. They fall through the opening together, into darkness. The floor is sticky. It’s warm. Hot, even. The feeling creeps back into his body. He rolls onto his back, the Prospector beside him. His chest burns. He can’t catch his breath. The Prospector pokes him in his side. “You got fat.” “You got skinny.” He pokes back. “It goes both ways.” “What does?” “Getting old.” They lie in silence for a while, like old friends or people who used to know each other. “You bring it?” He pulls out the papers. He can’t read anything in the dark, but he remembers the gist. “Seven figures.” “It’s worth more.” “That’s what they’re offering. It’s good money. Silver and gold, right?” “I don’t want it.” He remembers the message. Was it only last week? The satellite service and lag so bad he could hardly recognize the voice. “You asked me for help. You told me to organize a sale.” “I changed my mind.” “I came seven thousand kilometers! I cancelled patients!” His shouts don’t echo. The cave just eats up the sound. “Where the hell are we?” “Someplace warm.” A smell reaches him. A stink. He pulls off a glove and touches the floor. Sticky and hot. He staggers to his feet and pushes back through the opening. The ice has turned into a steady snowfall, but the wind’s died down. He sees the red slash of the cave opening. The snow stained in front of it, the blood already freezing black. He brushes some of the snow on the mound away, showing the white fur of his old friend. He reaches into his parka and touches the large tooth hung from a strap around his neck. His first patient. The Prospector stands beside him. “I still need your help.” “With what?” The Prospector doesn't answer. He tugs his toque down low over his eyes and pulls his pick out of the ice. He turns and walks off into the wastes. He doesn’t look back. He doesn’t have to. They both know the way home.  othing. He licks the edge of the pickaxe again. Still nothing. He brushes the snow off and gets back to his feet. Takes his time because it takes longer now. Even as the days dry up like raisins toward the end of the year, everything takes longer. And it hurts. Standing, walking, existing. It all hurts. He stamps his feet to get the blood moving, then grabs the chain and gives it a yank. The toothless beast at the other end moans, but with another hard pull it finally lumbers to its feet, breathing hard. The coast is only a short march now. Stagger is more like it. He misses the dogs, but they’d needed to eat. One by one, and then they’d burned the sled for firewood. They haven’t been warm since. The wind is picking up, blowing snow, his breath forming crystals in his moustache and beard. He’ll have to be careful. Not stop again. Not for the frostbite. He’s had so much of that his skin is like rawhide, but he has to watch out for chasms. The ice is cracking up more and more, chunks drifting off. Soon there’ll be nothing left. He promised to be at the landing by sundown. Sundown being a relative term having nothing to do with light and dark. Everything is black as coal, as pitch. Blacker even. Has been for weeks, would be for weeks more. But a few dozen steps are all he can manage. He drops the chain and the beast behind him settles gratefully to the ground with a thump and a groan. Out of habit or hope, he tosses his pickaxe in the air and lets it fall, point first in the ice. Maybe this time. He jerks it out and licks the edge. Still nothing. No whiff of menthol to tell him Dig, dig here. He gives the chain a yank. Then another. Then another. But it doesn’t move. It lies there: a giant mound of white fur. He keeps yanking, but it’s just another useless motion. Like breathing. He lets the chain go. It’s hard to tell the fur from all the snow around it. Already it’s been covered up. Once, it had been so wild and feared. Then he broke and tamed it. Now, it’s just another lump. He turns back. The journey has to go on. You can’t stop it. Like the year, hurtling toward an end. As it went on after the peppermint mine played out, and the elves went on strike, and Walmart bought the whole operation up and then shut it down. You just have to put one foot in front of the other. But underneath his feet, there’s a crunching and snapping. Like the bones of a giant. He falls back on his ass, lines spidering out through the ice, water leaping up through the cracks. He digs in with his cleats, pushing himself back from the edge. He’s reached the coast. Then, a bubble of light shows through the blowing snow. For a minute he thinks, This is it. A red light in the sky. Blinking. He almost shouts. Wahoo. He almost believes. Things won’t have to change. They’ll reverse. His friends will undie. The water will refreeze. The drills will rise and the oil rigs will retreat. But then there’s the slow, spinning sound of rotors above him to tell him there's no magic. It just goes on. Life. The helicopter descends. It’s relentless. He sticks the pickaxe in the ice to show them where to land. He buries it deep so it can’t be pulled up. Then he rubs his hands together and blows into them. He just needs a little feeling in his fingers so he can work a pen. So he can sign the contract.  he kicks through wet leaves. Orange and red, dying and dead. The streets are empty. All the children, their laughter and their shouts, are safely tucked away for another year. Butterscotch wrappers scattered in the gutters are all that remain. She follows the pools of lamplight, jumping in and out of darkness, like she has for most of her life. Nobody rang the bell again this year. Here, she climbs the wooden fence. Paint flaking, boards leaning like old men trying to catch their breath. She can’t hop it like she used to, barely breaking stride. She gets one leg over and her coat catches on a scab of wood. She gives it a yank, the seam tears and she lands on her ass in the dirt of the field. Nothing’s been sown here but weeds for the last twenty years and even those aren’t doing so well these days. There’d been some sort of run-off from the factory. Folks just bought their pumpkins from the supermarket nowadays. She finds him here at the far end of the field. Stretched out on the earth, his ratty blue blanket tucked under his head. His skin glows in the moonlight. So pale, you almost don’t notice the grey in his hair. His face looks so relaxed in sleep without all the tremors or tics. She plays with the torn seam on her coat. New this year, but now as ruined as anything she owns. Just like him. The neighbourhood kids have their jokes. If his failure weren’t so sincere, she’d laugh too. Coming out here, year after year. He’ll freeze to death if she doesn’t bring him home. She pulls the edge of the blanket up to cover her brother as best she can. They have a long walk ahead. But for now she’ll let him sleep. The disappointment of tomorrow could wait a while longer. |

8bitmythsRemember when you were a minipop, and you saw that film, you know, the one you loved that never had a sequel? Well, let's say it did. And it was just like you imagined it, only a little bit worse.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed