e looked through storage bins for hours, but he couldn’t find the boombox anywhere. By then it was the middle of the night and he’d lost most of his nerve. But not all of it. His nerve was like a cockroach after an atomic test. He found his grey trenchcoat. His Clash t-shirt. His body wasn’t a good fit for them anymore. He went out to the garage and pulled the cover off the Malibu. He was walking his life in reverse. He had to push the car down the drive, jumping in and coasting to get the engine to turn over. It was a long ride upstate. But he felt the town line roll underneath him like a dead animal. He slipped into the old ways easily. His nostalgia was inscribed into the Morse Code of potholes. The hypotenuse of a street lamp. Her parents’ house was just where they left it. He pulled up behind their SUV, parked in front. He looked at the stickers on the rear window. The dog, the two kids. But the woman stood alone. She was holding a fragment of someone’s hand. The arm and the rest of the body had been ripped clean off. He swung around and came up the next street, pulling up to the wooded lot at the back of the house. He turned the engine off. The car wouldn’t start again. He wouldn’t need it. He was all in. He was all out, too. He grabbed his cellphone and a plastic cup from the garbage on the floor. He swung out the door. The lights were off. There was a whisper of blue across the sky. Dawn was a rumour in an ugly barroom. He knew which window was hers. Had been hers when they were just kids. He skimmed through his playlist, found the song and dropped the phone into the cup. He held it up over his head with both hands. The music had the strength of a death rattle. He missed his boombox. A dog barked. Maybe he should get closer. But this was the pose, right here. This is what had worked before. And before. And before. It was like a magic spell. A red button. Someone else’s words for his mistakes. When it was over, he played it again, and put it on repeat. The light in her room stayed off. He imagined her anger was a great silence he was stabbing into. He would not give up. He would not give up on their love. It was like holding a rotten piece of fruit and willing it back to ripeness. One of the neighbours was out in a bathrobe, looking at him over the fence. She held a cordless phone like a live grenade in one hand. She was calling the police. She couldn’t tell the difference between perversion and love. He wanted to shout, to throw something, but he didn’t want to interrupt the song. This spell he was casting. His arms were getting tired. But he could hold on. She’d have to wake up eventually.

0 Comments

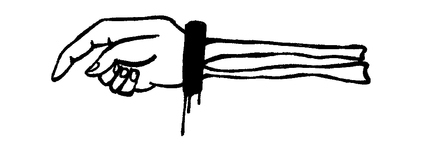

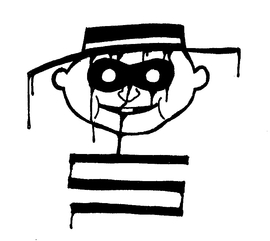

e grabbed the shovel from behind the garage and limped down the drive. He kept his back to the house, crouched there darkly in the snow. But he could feel the crack in the drapes. His mother’s eyes on him. They never left him alone. Not ever again. They worried, as people do. He was the youngest, after all. He needed special attention. They pulled him out of school and did his lessons at home. His father sold the firm and started a small consulting business on the side. His parents took turns going for groceries. He was never out of sight for long. If he sneezed, they’d put him to bed, feed him comic books and flattened ginger ale. Pile hot water bottles around him like sandbags. His brothers and sisters grew up, as people do. They left home, marching one by one. He was allowed to wave them off in the driveway, mother on one side and father on the other, hands latched to his shoulders. Around the corner they went, at the end of Lincoln Boulevard and on into their real lives. Some of them came back for summer vacations for a while. Now they were only a family occasionally, the way a rock skips across the dawn surface of a lake. Skip, a wedding. Skip, a baby shower. Skip, Christmas. Skip. This was the first year no one had come home. They never would again. Not in the same way. They sent Christmas cards instead from their own homes. The shovel scraped across the asphalt. They let him go this far, to the end of the drive. There was a timer going, back in the house. His mother had drawn up elaborate algorithms calculated to negative temperature and hypothermic probabilities. Winter was his favourite time. The snow dragging the trees down low to meet each other up and down the boulevard. The day dying fast behind the big hunched houses. He snapped his fingers. Wink, went the lights at 542 at the end of the street. Snap. On came 577. Snap, 602, closer. Snap, 613, closer still. He conducted comings and goings on the street. With the last layer of frost shaved from the drive, he pulled the aluminum trashcan out from beside the fence and began the salting, crisscrossing back and forth. The shovel had been given to him by his neighbour, when his granddaughter bought him a snowblower. It was a metal one, the kind they didn’t make anymore, with an edge like an ice skate. He remembered the stories about the old man, dead now many years back. He hacked his family into pieces with the shovel. Or so they said. Things seemed so much simpler back then. When he was done the asphalt glowed. It was like snow hadn’t even been invented yet. He snapped his fingers. The lights came on next door. He leaned on the shovel at the end of the drive. His toes edged up to the sidewalk. His back hurt. Most things hurt these days. He’d grown a beard. A long one. And at some point it had gone grey. He’d grown old, as people do. He turned back to the house, just as it flared up like all the Christmasses of his life. The lights were strung in the trees. The burnt strands loomed high, where the branches had carried them to die. He clomped up the drive, dragging the shovel behind him. The metal made a sound like a fork across a dinner plate. Somewhere in there his parents were wrapping the very last of the presents. They took care of him, as people do. Really good care. One day, it would be his turn.  n the tunnel in five, Joe,” his manager said, words that hit him in the gut more than the blows to come. He wrapped his hands again and unwrapped them again. Not for luck. Luck was something for people who still had a hope. Maybe today he’d make it a few rounds. Maybe he’d go down in the first. He was tired. He could use a nap. Or a coma. He couldn’t remember winning, but it happened. Once. The first. He was never much good with the hook, but that day in Bousillé-Bèze he took Halimi down with one punch. Of course he was as good as retired by then, half-blind, but no matter. Those were the days. He was making a name for himself. Joël L’incassable. Unbreakable. Even when he lost, the crowd was on his side. In Paris, they rushed the ring and tried to tear the judges apart. The publicity got him all the way to the States for a title match. But a good shot to his jaw took him down a second time. Something broke. And when he healed up it stayed broke. And he stayed on, broke and broken in Brooklyn. The first few losses hurt, because he tried. The next ten or so were pillowed with bills. After that, he lost count. Sometimes he tried, sometimes he took the fall, sometimes he didn’t know which he was, on or off. He’d flutter between punches like a film reel. Jab. On. Hook. Off. He let the wrapping alone and pulled the gloves on. He put on the robe. The colours had run and he couldn’t afford a new one. He looked down the hall. The lights of the stadium. He didn’t even know who he’d be losing to. He walked. It was that one win that stung. It never changed. 1-99 or 1-999 it was still there, weaving and dancing just out of reach. It would be easier to be zero. Vanquished. The crowd wasn’t roaring. This wasn’t the kind of place that roared. It mumbled. When he lost, they’d shout names. They’d throw croissants at him. They didn’t look anything like the ones back home. Just soggy supermarket pastry. But they still hurt. They still found things to break.  hen they brought him back home, she swore. She used every blue word in the book. She said things that would make sailors head for the desert. It didn’t seem to matter anymore. Cursings and blessings had been a mixed bag for the two of them. She had no idea which one they were now. They had a few wonderful years. At first they stayed awake day and night, enjoying the kind of delirious love only the sleep-deprived can understand. Each passing of day and night, they felt desperate. They clung to each other like ivy on a crumbling wall. Then they fought. You’re always pecking at me, he complained, playing the sharp consonants of the word with beaked fingers. She grew to hate the way he ate. Close your mouth if you’re going to wolf it down like that, she’d say. They were always careful to choose the words that could do the most damage. It was the kind of instinct common to beasts of prey. In the end he started taking long walks at night. He’d stay out longer and longer. She’d lie awake in bed, listening for the sound of him on the path. Two legs or four tonight, she’d wonder. Then one night he didn’t come back. Two brothers found him in a field down the road, humping a sheep, and put two arrows in him. Strange, they said. Usually wolves go for the throat. When the dawn broke like an old egg on the hills and he turned back into a man, they felt rather awkward. They carried him back home in a wheelbarrow, but she wouldn’t let his body in the house. Bury him in the yard, she said. That’s what you do with dogs.  t was strange the way he’d been found, the officer said. Pulled apart like focaccia. The coroner said it was like an animal attack he’d seen at the zoo, but the door to the apartment was locked from the inside and there was nothing out the window but a lot of air. There was a bowl and a spoon on the kitchen table. It was like a riddle. They had the pieces safely stowed in a body bag before the parents arrived, but there was nothing they could do about the carpet. Like a torrent of arrabbiata, the officer said, suddenly hungry. His mother wept soundlessly and dry. His father checked the water pressure in the kitchen. How do they get it so good this high up, he said. What, said his mother. He had been the least favourite of their children, but he was still blood. He was only blood now. What a mess, his mother said, picking a hat off the floor. Big and blue, the kind of thing someone would wear with an eyepatch to a costume party. She put it in the laundry hamper and then started separating his colours. What a mess, she said again. His father checked the kitchen cupboards. Need a little oil there, he said. What, said his mother. Need a little oil, said his father louder. I can’t hear you, she said. There were boxes of cereal. Boxes and boxes. None of the ones they’d weaned him on. Shredded, puffed, creamed and rolled: a childhood without taste. Instead here was a circus of brightly coloured cardboard. Looped and flaked and frosted and crisped and sugared. Not an oat in sight. Diabetes, his mother said. That’s what it must’ve been. But his father was already off checking the water pressure in the bathroom. Twenty storeys up, he was thinking to himself. The neighbours later reported hearing things the night before. The cawing of some exotic bird, the growling of a large cat, the snap, crackle and crunch of bone. A rabbit was found loose in the hall. He hadn’t owned any pets. His parents wouldn’t let him. You might have allergies, his mother had said. Dear —,

For a year, I wrote a story every Monday (false – there were those three Mondays when I couldn’t because: 1. I was lost in the woods, 2. I was Christmassing, and 3. I just didn’t feel like it). Here we are at number 52, and it seems like a good time to take a wee break. 8bitmyths started as an exercise for myself. A deadline to keep me efficient, writing something small every week. Sometimes the stories took seven minutes and thirty-eight seconds to write, other times I fell asleep at my keyboard. There are a lot of things I do that don’t make sense. I don’t shave enough, I don’t have a real job, I spend too much time in the past. I’m a nostalgist. There’s something about the past that brings me back into alignment. Growing up took a lot out of me, and I’m still Humpty Dumptying it all back together. 8bitmyths has been a chance to look at all things I loved—books, movies, television shows, toys—and analyze how they shaped me. How I got to the now, now that the now has passed. The other thing it gives me is a chance to take off the rosy Ray-Bans and look at the past right in its ugly acid-washed face. A lot of those things I loved…they were actually pretty awful. I mean, have you watched Thundercats lately? Mostly, though, these stories are a chance to play in the big backyard of life. All this to mumble: I’m still writing. I’ll still be posting 8bitmyths, just not every Monday. And if you feel like it, if you ever want to, you can electronic mail me some of the things you loved growing up, and I can write an 8bitmyth about them. Most likely, I will maim or murder your favourite character(s). But it will be done with love. ~M.  he story was going to end. It said right on the cover that it wouldn’t, but he’d had a lifetime of experiences with false advertisements and broken promises. Love you forever, like you for always. Sure, he could see there were a lot of pages, a lot more than most of the books he’d read, but the amount was measurable. Finite. The grim inevitability had sank in as the sun sunk down. There had been a lot of sinking in his life of late. Hairlines, belt lines. Punchlines. None of the borders he’d drawn seemed solid. So, after supper and before indigestion, he got in his car and drove downtown. Winding his way in from the suburbs, like a brook trout fighting upstream. The bookshop was gone, of course. Just another empty storefront on the main drag. But he didn’t need it. He never returned the book. It was in a plastic grocery bag in the backseat. They’d wrapped the school in chainlink, but he found his way under, ripping his shirt and then cutting his hand struggling through a broken basement window. He was covered in blood, cobwebs and years. The halls were hollow and hallowed and the place reeked of memory. He walked with his head bowed, like a monk in ceremony, filing past the procession of lockers. He thought of mistakes and missed opportunities. He took a piss in the girls’ washroom on the third floor. There was no one to tell him not to. He had to bust the lock on the attic. He climbed the old stairs. He found an old blanket. He lit an old stump of candle. He sat down on the old wooden floor. Everything old, just like old times. Only he was also old this time. He read and remembered most of it. It seemed shorter. Smaller. They were just words on the page. A rectangular object. The magic in it was gone. It was that bare nub of dandelion after the dust had blown away. And here he was. Ten or twenty pages left. Then he’d have to go. Back up those streets, driving not flying, where there’d be no bullies waiting to throw him in a dumpster. They’d moved on. Got real jobs. They didn't miss him. Not the way he did, with a fierce and clutching love, for them and all the lost comrades that now seemed to loom from every dark corner of the attic. It wasn’t a bad book. It was just ending. Like everything. He was all grown up, there was nothing he could do about it. Nothing.  t’s been another one of those days that take everything you got and a little bit more. You’re walking down rain-wrought streets, inner city symphony and you’re oh so weary. Too weary to go home and face your four walls. Your stack of bills, dusty rusted life. You just want to take a break from all these worries. So you tuck in here, following a sign, the hand pointing you downward a short flight of steps. You reach a door, thick, wood hardened by time and salt. There’s a small pane of glass cut into it, frosted, but when you lean your forearm against it you see light and colour. You imagine making this your place. Putting in your time, coming every day, day after day until you can use words like Regular and Usual. You’ll pull up a stool, put a foot on the rail and a pint will be waiting. You’ll get relationship advice from the bartender. You’ll banter with the barbed-wire gargling, heart of gold waitress. You’ll swap war stories with the resident experts. You’ll see that your troubles are all the same. You’ll be balm for each other’s pain. It’s cold out here, so you push through the door, into warmth and noise. It’s everything you pictured. Dark oiled bar like a brass-railed schooner on a terrazzo sea. Only, it’s empty. Nobody shouts your name at your arrival. No one returns from a game of darts in the back to buy you a round. There are two college kids in ball caps, sitting in a booth watching the game on the teevee. They don’t even notice you. They’re not glad you came. It’s just another bar full of old glory gone sour in the taps. You just want to get away.  e’d done ten years and he’d done them hard, upstate. It’d been especially hard on him, hammering away at his cherubic face, his buck-toothed smiled. He was now just a collection of right angles. They gave him a plastic bag with his clothes. The brim of his hat was all bent out of shape. There was no one there to meet him. They dropped him off at the bus station on the outskirts and stuck a pamphlet in his hand. He wandered until he found a driver outside on the platform, having a smoke. There was a blue tattoo on his forearm, too smudged to make out anymore. He understood. He took him downtown. Everything seemed so fast. People, cars. The world in fast forward, and him stuck on rewind. He found the shelter, a hump of brick squatting on the corner. There was a park across the street, but not the kind you’d want to walk in without a HAZMAT suit. They put him in a room with three other guys. The food was bad. Things hadn’t changed much. He went to see his parole officer. They set him up with a job, just down the street from the shelter, cleaning a burger joint after hours. The sign only had one arch, instead of two, and it was so rusty you could hardly call it golden. Still it was like throwing him in a candy shop full of razor blades. Maybe they did it just to screw with him. At the end of his shift, he’d sit in the change room, naked. He’d put on the cape, the hat and the red gloves. He’d imagine the sound of grease popping as the slabs of meat fried. He could still smell it. It would be so easy. Just one bite. But that’d be the end of him, he’d tell himself, pretending it wasn’t all over already.  he has her back to the wall, eye on the door, like some old prizefighter catching a breath. It’s a good vantage point to watch the women in last year’s fashion and men with none at all mingle in the dim light, their conversation dimmer still. The band, more out of tune than touch, is playing a black hole into the dance floor. The food, at least, is sufferable. John is out there, somewhere, dazzling some young thing with his Cheshire smile. She scans the crowd, eyes hungry. Maybe the next song. Maybe the one after. Something would get her moving. A toe tap, or two. A head bob. A shoulder dip. Then up on her feet, hipshake, gyrate, make her way between the tables, march one two, sucking up stragglers, a few, three four, a few more, fingers snapping, feet stamping, clearing out the dance floor, to soar soar soar, again. The gin sour burns a trail down the back of her throat. She puts the highball down and settles back into the corner. The band finishes another bitter number. Maybe this next song. Maybe the one after. |

8bitmythsRemember when you were a minipop, and you saw that film, you know, the one you loved that never had a sequel? Well, let's say it did. And it was just like you imagined it, only a little bit worse.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed