e looked through storage bins for hours, but he couldn’t find the boombox anywhere. By then it was the middle of the night and he’d lost most of his nerve. But not all of it. His nerve was like a cockroach after an atomic test. He found his grey trenchcoat. His Clash t-shirt. His body wasn’t a good fit for them anymore. He went out to the garage and pulled the cover off the Malibu. He was walking his life in reverse. He had to push the car down the drive, jumping in and coasting to get the engine to turn over. It was a long ride upstate. But he felt the town line roll underneath him like a dead animal. He slipped into the old ways easily. His nostalgia was inscribed into the Morse Code of potholes. The hypotenuse of a street lamp. Her parents’ house was just where they left it. He pulled up behind their SUV, parked in front. He looked at the stickers on the rear window. The dog, the two kids. But the woman stood alone. She was holding a fragment of someone’s hand. The arm and the rest of the body had been ripped clean off. He swung around and came up the next street, pulling up to the wooded lot at the back of the house. He turned the engine off. The car wouldn’t start again. He wouldn’t need it. He was all in. He was all out, too. He grabbed his cellphone and a plastic cup from the garbage on the floor. He swung out the door. The lights were off. There was a whisper of blue across the sky. Dawn was a rumour in an ugly barroom. He knew which window was hers. Had been hers when they were just kids. He skimmed through his playlist, found the song and dropped the phone into the cup. He held it up over his head with both hands. The music had the strength of a death rattle. He missed his boombox. A dog barked. Maybe he should get closer. But this was the pose, right here. This is what had worked before. And before. And before. It was like a magic spell. A red button. Someone else’s words for his mistakes. When it was over, he played it again, and put it on repeat. The light in her room stayed off. He imagined her anger was a great silence he was stabbing into. He would not give up. He would not give up on their love. It was like holding a rotten piece of fruit and willing it back to ripeness. One of the neighbours was out in a bathrobe, looking at him over the fence. She held a cordless phone like a live grenade in one hand. She was calling the police. She couldn’t tell the difference between perversion and love. He wanted to shout, to throw something, but he didn’t want to interrupt the song. This spell he was casting. His arms were getting tired. But he could hold on. She’d have to wake up eventually.

0 Comments

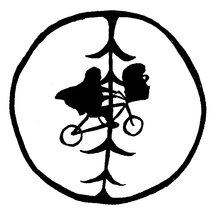

e grabbed the shovel from behind the garage and limped down the drive. He kept his back to the house, crouched there darkly in the snow. But he could feel the crack in the drapes. His mother’s eyes on him. They never left him alone. Not ever again. They worried, as people do. He was the youngest, after all. He needed special attention. They pulled him out of school and did his lessons at home. His father sold the firm and started a small consulting business on the side. His parents took turns going for groceries. He was never out of sight for long. If he sneezed, they’d put him to bed, feed him comic books and flattened ginger ale. Pile hot water bottles around him like sandbags. His brothers and sisters grew up, as people do. They left home, marching one by one. He was allowed to wave them off in the driveway, mother on one side and father on the other, hands latched to his shoulders. Around the corner they went, at the end of Lincoln Boulevard and on into their real lives. Some of them came back for summer vacations for a while. Now they were only a family occasionally, the way a rock skips across the dawn surface of a lake. Skip, a wedding. Skip, a baby shower. Skip, Christmas. Skip. This was the first year no one had come home. They never would again. Not in the same way. They sent Christmas cards instead from their own homes. The shovel scraped across the asphalt. They let him go this far, to the end of the drive. There was a timer going, back in the house. His mother had drawn up elaborate algorithms calculated to negative temperature and hypothermic probabilities. Winter was his favourite time. The snow dragging the trees down low to meet each other up and down the boulevard. The day dying fast behind the big hunched houses. He snapped his fingers. Wink, went the lights at 542 at the end of the street. Snap. On came 577. Snap, 602, closer. Snap, 613, closer still. He conducted comings and goings on the street. With the last layer of frost shaved from the drive, he pulled the aluminum trashcan out from beside the fence and began the salting, crisscrossing back and forth. The shovel had been given to him by his neighbour, when his granddaughter bought him a snowblower. It was a metal one, the kind they didn’t make anymore, with an edge like an ice skate. He remembered the stories about the old man, dead now many years back. He hacked his family into pieces with the shovel. Or so they said. Things seemed so much simpler back then. When he was done the asphalt glowed. It was like snow hadn’t even been invented yet. He snapped his fingers. The lights came on next door. He leaned on the shovel at the end of the drive. His toes edged up to the sidewalk. His back hurt. Most things hurt these days. He’d grown a beard. A long one. And at some point it had gone grey. He’d grown old, as people do. He turned back to the house, just as it flared up like all the Christmasses of his life. The lights were strung in the trees. The burnt strands loomed high, where the branches had carried them to die. He clomped up the drive, dragging the shovel behind him. The metal made a sound like a fork across a dinner plate. Somewhere in there his parents were wrapping the very last of the presents. They took care of him, as people do. Really good care. One day, it would be his turn.  hen they brought him back home, she swore. She used every blue word in the book. She said things that would make sailors head for the desert. It didn’t seem to matter anymore. Cursings and blessings had been a mixed bag for the two of them. She had no idea which one they were now. They had a few wonderful years. At first they stayed awake day and night, enjoying the kind of delirious love only the sleep-deprived can understand. Each passing of day and night, they felt desperate. They clung to each other like ivy on a crumbling wall. Then they fought. You’re always pecking at me, he complained, playing the sharp consonants of the word with beaked fingers. She grew to hate the way he ate. Close your mouth if you’re going to wolf it down like that, she’d say. They were always careful to choose the words that could do the most damage. It was the kind of instinct common to beasts of prey. In the end he started taking long walks at night. He’d stay out longer and longer. She’d lie awake in bed, listening for the sound of him on the path. Two legs or four tonight, she’d wonder. Then one night he didn’t come back. Two brothers found him in a field down the road, humping a sheep, and put two arrows in him. Strange, they said. Usually wolves go for the throat. When the dawn broke like an old egg on the hills and he turned back into a man, they felt rather awkward. They carried him back home in a wheelbarrow, but she wouldn’t let his body in the house. Bury him in the yard, she said. That’s what you do with dogs.  he story was going to end. It said right on the cover that it wouldn’t, but he’d had a lifetime of experiences with false advertisements and broken promises. Love you forever, like you for always. Sure, he could see there were a lot of pages, a lot more than most of the books he’d read, but the amount was measurable. Finite. The grim inevitability had sank in as the sun sunk down. There had been a lot of sinking in his life of late. Hairlines, belt lines. Punchlines. None of the borders he’d drawn seemed solid. So, after supper and before indigestion, he got in his car and drove downtown. Winding his way in from the suburbs, like a brook trout fighting upstream. The bookshop was gone, of course. Just another empty storefront on the main drag. But he didn’t need it. He never returned the book. It was in a plastic grocery bag in the backseat. They’d wrapped the school in chainlink, but he found his way under, ripping his shirt and then cutting his hand struggling through a broken basement window. He was covered in blood, cobwebs and years. The halls were hollow and hallowed and the place reeked of memory. He walked with his head bowed, like a monk in ceremony, filing past the procession of lockers. He thought of mistakes and missed opportunities. He took a piss in the girls’ washroom on the third floor. There was no one to tell him not to. He had to bust the lock on the attic. He climbed the old stairs. He found an old blanket. He lit an old stump of candle. He sat down on the old wooden floor. Everything old, just like old times. Only he was also old this time. He read and remembered most of it. It seemed shorter. Smaller. They were just words on the page. A rectangular object. The magic in it was gone. It was that bare nub of dandelion after the dust had blown away. And here he was. Ten or twenty pages left. Then he’d have to go. Back up those streets, driving not flying, where there’d be no bullies waiting to throw him in a dumpster. They’d moved on. Got real jobs. They didn't miss him. Not the way he did, with a fierce and clutching love, for them and all the lost comrades that now seemed to loom from every dark corner of the attic. It wasn’t a bad book. It was just ending. Like everything. He was all grown up, there was nothing he could do about it. Nothing.  he has her back to the wall, eye on the door, like some old prizefighter catching a breath. It’s a good vantage point to watch the women in last year’s fashion and men with none at all mingle in the dim light, their conversation dimmer still. The band, more out of tune than touch, is playing a black hole into the dance floor. The food, at least, is sufferable. John is out there, somewhere, dazzling some young thing with his Cheshire smile. She scans the crowd, eyes hungry. Maybe the next song. Maybe the one after. Something would get her moving. A toe tap, or two. A head bob. A shoulder dip. Then up on her feet, hipshake, gyrate, make her way between the tables, march one two, sucking up stragglers, a few, three four, a few more, fingers snapping, feet stamping, clearing out the dance floor, to soar soar soar, again. The gin sour burns a trail down the back of her throat. She puts the highball down and settles back into the corner. The band finishes another bitter number. Maybe this next song. Maybe the one after.  ating disorder, the vet says. Legs up on the desk, hands behind her head. Real common, you could try it on a different food. Tried that, doc. You could try switching up mealtimes, she says picking her teeth. Feed it at night instead of mornings. Can’t do that, doc. Early riser, eh? Happens to men as they get older. It’s not that. I can’t sleep a damn anyway. But I got to keep him on a schedule. Okay then, she says spreading her hands on the desk in surrender. You could take it to a psychologist. They have those for pets now, you know. Cost you a fortune. No thanks, he stands in the doorway. Say, doc, what do you call those animals that don’t reproduce. Like the normal way. She leans forward, What kind of animal you say this was again? Exotic. He tips his ballcap, Thanks, doc. Parthenogenesis, she says as the door swings closed. He does the rounds, emptying the dehumidifiers in each room and setting them to high. It was a hot one outside, these early days of summer. But you’d never know it in here. There’s a certain kind of smell that the black garbage bags taped to the windows give off as they cook in the sun. In the kitchen, he checks the clock on the stove, an old habit, as he dumps some kibble into the red plastic bowl and heads up to the attic. Over the years his eyes have adjusted to the dark. He finds the door to the cage and opens it. At the back he can just make out the wet circles of its eyes. Come on, buddy, he says, You got to eat. It crawls forward, gives the food a sniff and then pushes the bowl away. Its hair has come out in patches, and now it looks like a pink little ragdoll. Its ears droop like butterfly wings. Don’t look at me like that, he says, It’s not my fault. He stomps back downstairs with the bowl. Dumps it in the trash. But maybe it is his fault. He’s broken all the rules. There were just so many. Don’t do this, don’t do that. When you look too hard at any of it you go cross-eyed. He hears something upstairs. A song? No. The house has been silent for years. It didn’t sing to him anymore. Not because of the rules, at all. He knows the truth. It was just lonely. He starts to cook. Chicken drumsticks, the way his mom used to do them. He watches the clock on the stove crawl toward midnight. They were both just so lonely.  e drags the bike up to the edge. It’s about twenty feet down. Enough to end it if you wanted it bad enough. The sun’s a bloody thumbprint. Smearing down, down. Rooftops now where there used to be trees. He drops the bike in the dirt. A child’s toy, even then. A museum piece, now. The frame barnacled in rust, the milk crate cracked with age. His kids had never bothered with it much. But he had never bothered much with them either. Even less as they got older. Drifting like icebergs or galaxies. He held them in his hands, swaddled in blankets, kissed their skin. But he could never feel close enough. People make promises they can’t keep. Politicians, presidents and prime ministers. Human beings, too. I love you. I will never leave you. Afterwards, it was all science and misunderstandings. We would never hurt a boy, they said. All we had were walkie-talkies. But he remembers looking down the barrel of a gun. Monsters in plastic suits. A child’s imagination, they said. The promises broken. I’ll be right here. That’s what it had said. The man in the moon. It had pointed at his head. Right here. And then it left him anyway. Never came back. Never phoned. For years, every time he got sick he wondered. When a pain would hit him out of nowhere. Were they still connected like two tin cans and a string of twine. When he was lonesome. When he farted. But then he saw the scans. The doctor didn’t notice. She slipped out of the room to take a call and he flipped the file open. Held the glossy sheets up to the light. There in the center of his brain: another small planet in orbit. Growing. The moon is rising. He picks up the bike and sits on the seat, rocking back and forth on the wheels, kicking dirt down on the rocks below. He pulls the red sweatshirt down over his gut, puts his feet on the pedals. His knees are so high he’s practically fetal. For years he’s dreamed of flying through the sky, swimming through the milk of the moon. Now he’s falling through space. That glowing finger jabbing at his head. Not a lie, a threat. An invasion. I’ll be right here.  o one accused him of being the world’s best father. His kids had been in and out of therapy for years. He’d used them for his own experiments, it was true. And he’d almost eaten his son in a spoonful of cereal. But not on purpose. It didn't matter that he tried his best. He always made the child support payments on time. They wouldn’t speak to him anymore. He left messages. He kept scrapbooks, meticulously filed, bragged about every one of their accomplishments to the neighbours. When they’d listen. The university had pulled the funding years ago. It was a forced retirement. He’d expected, like from out of one of those old B movies, that some general would show up on his lawn in a Sherman tank and demand the plans for his machines. They’d blast the shrinking ray at whatever nation had the most oil, or make 50-foot soldiers. But it never happened. It was always easier to blow things up the old fashioned way. All he cared about were his children. He thought, if I could only invent something to make them happy. Protect them from pain. He rehearsed the line, You were my greatest inventions, over and over, but he never got to use it. He still spent most days and nights in the attic, toiling away. Tinkering. Building up, breaking down, rebuilding. Every day was a new kind of ruin.  e limps between the tombstones, the few not crumbling or knocked over by teens. He isn’t as tall as he used to be. That’s what age does to you. Curves the spine, rounds the joints, shaves off inches and memory. Makes you somebody else. He keeps to himself these days. The dwarves organized on him, started insisting on being called Little People and demanded new robes. Cotton instead of the burlap he’d been buying in bulk. Too itchy, they said. So he just stopped making minions altogether. He’d let the spheres rust, too. He couldn’t afford to fix the humidifier to keep the old place dry. Mausoleums cost a fortune to heat. He’s taken to snowbirding. At the first sign of frost, he’s off to the red dimension. He doesn’t come back until the asphalt shimmers. He has to take tests every year to keep the hearse on the road. The fat man from the DMV always sweating all over the leather, he’s almost happy when they come to blow it up now, so he can get a new one. And come they will. They always find him, eventually. There were only so many funeral homes, tombs and graveyards he could hide in these days. Back inside, he lays the brochures out on his desk. Maybe he could get a part-time job at the hardware store in town. Just enough to put a down payment on a condominium, in one of these seniors' places. Retirement home. It has a nice ring to it. But first, there’s sod to lay, floors to polish, brains to obtain. There’s never enough time. Today is quiet, sure. But tomorrow, or next week, one day soon they’ll come roaring up in that Barracuda, tearing up his grass. The boy and the ice cream man. Going on thirty years, but they just won’t give up. The irony doesn’t escape him. He’s short and the boy’s old enough to start collecting a pension. They’ll make a mess of the place. Whooping and hollering and firing off that four-barreled shotgun. He’s so tired of dying, he just wants to rest.  e likes his showers hot. He likes it to burn. After, he wipes the fog on the mirror with his hand and gets a glimpse. Nothing of the cherubic young boy left. He has another long day of meetings ahead of him. Sitting, listening vaguely, nodding. Doling out limp orders like a cafeteria slop server. He’d drag himself home after dark. Make a martini, sit on the couch and watch the news. Pet the dog, if it wasn’t off terrorizing someone. He shaves, the razor stumbling over stubble. Things had been easier when he was younger. Before shaving. Sure, there was the pressure of potential that all children feel, and he felt it more than most. But there was still time to play. Time to be free. And, of course, time enough to entice a nanny into suicide, now and then. He wraps a towel around his growing middle and opens the door to the bedroom, steam following on his heels. His clothes are laid out neatly on the bed. Ready for work, or a casket. When he was a kid, wearing a suit was special. Like playing at being grown-up. Just like carrying a butcher’s knife and smiling was special when you can’t even reach the counter. He’d been the next Antichrist. Now he was just another middle-aged savage in a sea of murderers. |

8bitmythsRemember when you were a minipop, and you saw that film, you know, the one you loved that never had a sequel? Well, let's say it did. And it was just like you imagined it, only a little bit worse.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed