t was strange the way he’d been found, the officer said. Pulled apart like focaccia. The coroner said it was like an animal attack he’d seen at the zoo, but the door to the apartment was locked from the inside and there was nothing out the window but a lot of air. There was a bowl and a spoon on the kitchen table. It was like a riddle. They had the pieces safely stowed in a body bag before the parents arrived, but there was nothing they could do about the carpet. Like a torrent of arrabbiata, the officer said, suddenly hungry. His mother wept soundlessly and dry. His father checked the water pressure in the kitchen. How do they get it so good this high up, he said. What, said his mother. He had been the least favourite of their children, but he was still blood. He was only blood now. What a mess, his mother said, picking a hat off the floor. Big and blue, the kind of thing someone would wear with an eyepatch to a costume party. She put it in the laundry hamper and then started separating his colours. What a mess, she said again. His father checked the kitchen cupboards. Need a little oil there, he said. What, said his mother. Need a little oil, said his father louder. I can’t hear you, she said. There were boxes of cereal. Boxes and boxes. None of the ones they’d weaned him on. Shredded, puffed, creamed and rolled: a childhood without taste. Instead here was a circus of brightly coloured cardboard. Looped and flaked and frosted and crisped and sugared. Not an oat in sight. Diabetes, his mother said. That’s what it must’ve been. But his father was already off checking the water pressure in the bathroom. Twenty storeys up, he was thinking to himself. The neighbours later reported hearing things the night before. The cawing of some exotic bird, the growling of a large cat, the snap, crackle and crunch of bone. A rabbit was found loose in the hall. He hadn’t owned any pets. His parents wouldn’t let him. You might have allergies, his mother had said.

0 Comments

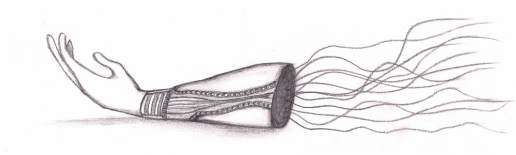

e’d done ten years and he’d done them hard, upstate. It’d been especially hard on him, hammering away at his cherubic face, his buck-toothed smiled. He was now just a collection of right angles. They gave him a plastic bag with his clothes. The brim of his hat was all bent out of shape. There was no one there to meet him. They dropped him off at the bus station on the outskirts and stuck a pamphlet in his hand. He wandered until he found a driver outside on the platform, having a smoke. There was a blue tattoo on his forearm, too smudged to make out anymore. He understood. He took him downtown. Everything seemed so fast. People, cars. The world in fast forward, and him stuck on rewind. He found the shelter, a hump of brick squatting on the corner. There was a park across the street, but not the kind you’d want to walk in without a HAZMAT suit. They put him in a room with three other guys. The food was bad. Things hadn’t changed much. He went to see his parole officer. They set him up with a job, just down the street from the shelter, cleaning a burger joint after hours. The sign only had one arch, instead of two, and it was so rusty you could hardly call it golden. Still it was like throwing him in a candy shop full of razor blades. Maybe they did it just to screw with him. At the end of his shift, he’d sit in the change room, naked. He’d put on the cape, the hat and the red gloves. He’d imagine the sound of grease popping as the slabs of meat fried. He could still smell it. It would be so easy. Just one bite. But that’d be the end of him, he’d tell himself, pretending it wasn’t all over already.  e’d slimmed out. Stopped eating junk food. He ran every morning. He got a degree, and then another one. He found a job. Not one he loved, but he made decent money and the holidays were nice. He married someone who saw the good in him and treated him well. They were talking about having a kid. Maybe two. His parents were proud of him. People liked him. He was loved by the few that matter. But still, sometimes a stranger, walking by him on a street, would stop, turn back and watch him go. They’d shake their head. He could be beautiful, they’d think, if he’d just stop eating chocolate bars.  he hits the horn again, aimed at no one in particular, knowing it will have no effect except to make the world around her just a little bit worse. Here she is, trapped in gridlock with no end in sight. For most people, it’s an inconvenience. Just another necessary evil in a long bastard of a day. For her, it’s life or death. This is the way she feels about everything, all day long. Somehow she keeps on living. This time, though, she could lose her job. She looks at the clock. Seven minutes left. If she gets there late, at best they’ll take it out of her pay. Again. She puts her hand on the lid of the cardboard box in the passenger seat. Lukewarm and fading. And there goes her tip, too. The right lane opens up and she makes her move, hitting the gas and swerving in front of a rusty old Civic. She flashes the finger in the rearview before the other driver can honk. Her lane is wide open ahead. She’ll show them thirty minutes or less. She crushes the pedal, flashing by all the gawking commuters on her left. Then she sees a flash of orange dead ahead and realizes why the lane was so open in the first place. She waits until the last minute and then screeches to a stop. The sound shocks the driver of the hatchback on her left enough that she can jam herself in front before he can do anything about it. A green sign above, like a beacon on a rocky coast, tells her the exit is just another hundred metres or so. Four minutes left, time for extraordinary measures. She swerves left into the carpool lane, accepting honks from all comers. They don’t know she has a passenger. Twelve slices of cheese and pepperoni. Cheese already stiffening in rigor mortis as it cools. She jumps ahead a few more car lengths and then hops right, then left, right again, more honking, screeching tires, brushing bumpers, windows rolling, new curse words birthed, and then there she is—running up the ramp to freedom. All that mess left behind her for someone else to deal with. Two minutes left. Just enough time. To make the right on Broadview, make the left onto Victor, make it to fifty-four just in time. She pulls through the stop sign without looking and something crashes onto the hood of her car, windshield spidering with cracks. She jams on the brakes, but whatever she’s hit grabs a hold of the wipers to keep from falling off. A man. A man in red spandex, mask over his eyes and rabbit ears. He’s pressed against the remains of the windshield, staring at her, cross-eyed, with a grin like an escaped mental patient. She looks at the clock. She’s going to be late. It can’t be avoided. All she can do is feel annoyed.  hen one day he just couldn’t put his arm back on. For years he’d been backflipping and somersaulting from one place to the next. It was pretty much the only way you could get around when your entire neighbourhood was constructed from lethal machinery. Every so often, he’d get snagged in a giant gear or caught in a saw blade. Sure, that’d tear a limb clean off, but it was better than the pools of magma. You couldn’t put it back on once it’d melted. All in all, Planet Danger wasn’t really the greatest place to live. He used to be able to snap it back on. Just like that, good as new. It was a trick he’d employ to impress his friends. But in the end they all got vaporized in the laser field. They didn’t play safe like he told them to. Lately, within the last eon or so, his arm just started falling off the minute he snapped it into place. He had never failed at anything before. Now he was regularly failing at putting his arm back on. It disturbed him for many cycles. Eventually, he buried the damned thing under a pile of razor wire and broken glass. He kept waiting for further failures. It seemed inevitable now. |

8bitmythsRemember when you were a minipop, and you saw that film, you know, the one you loved that never had a sequel? Well, let's say it did. And it was just like you imagined it, only a little bit worse.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed