|

He finds what used to be the only sushi place in the Lower East Side and orders seaweed salad and a tall can of Asahi. He puts the yellow piece of paper with its invitation on the fake bamboo table in front of him. He eats and drinks slowly, watching the sunset trickle down the brick tenements across the street. This used to be a ritual for him, before a fight. Tonight, he follows the ritual again, like a walk down an old street, the memory of a first kiss, the taste of your own blood.

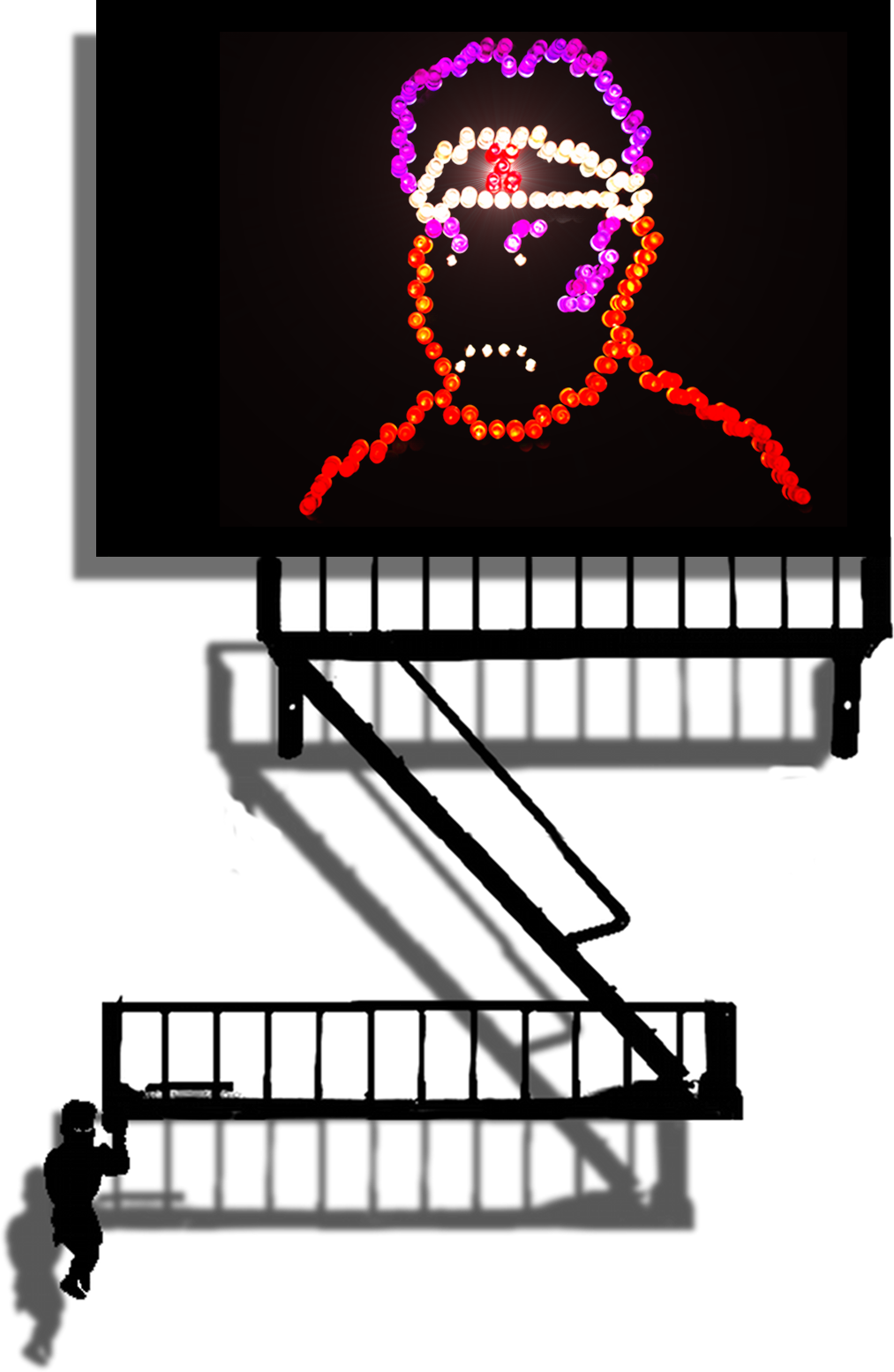

Soon there would be a crowd. Noise. He likes to be alone beforehand. Back home it had been impossible. Strangers shouted his name across busy intersections. He had a constant entourage. Flashbulbs, video cameras and microphones surrounded him like old enemies. Every contour of his face was charted, every wiggle of his eyebrows gauged like seismic shifts. When the American came to his dressing room after his fifth title defense, he waved away his manager, his publicist, his consultants and bodyguards. He didn’t need a translator. He didn’t bow. They shook hands. He was on a plane the next day. The American wanted him to fight on the west coast. Lots of your folks there, he said, And you can almost see home across the Pacific. Like he was homesick. He was at home in the ring, nowhere else. But he went. Seattle, San Francisco. L.A. It didn’t matter where. People came to see him like packs of wild pigs, waving flags and homemade banners written in kanji. Local stations wanted to interview him on air in Japanese. He went up and down the coast, trying to get away from the crowds, until there was no one left to knock down. Send me somewhere I can be alone, he said. So they sent him to the biggest city in North America, and here he is, three decades later. New York. He sips the beer, rolling its coldness around in his mouth, tracing it down his throat, feeling the ritual revolving inside him. The sun has reached the lower edge of the fire escapes, throwing shadows like busted rib cages. A few more inches to go. A man pushes a grocery cart through the gutter, raving at people around him, but nobody turns. No one hears his decrees. He likes the anonymity of the city. It’s something he can slide over himself like a bubble of liquid glass. Even at rush hour, when the streets spill over, people maintain a sliver of space between their body and the next. He imagines a camera zooming out above the city, showing millions of glass marbles rolling up and down the arteries of city streets, none of them touching. When the server comes with the bill, she also slides a glossy 8x10 across the table. He almost doesn’t recognize the face. His own. Young. This is not ritual. Rituals are sameness. This is younger than he’s ever been. She doesn’t look at the floor while he signs the photograph. Maybe it’s for an uncle who remembers him from the NHK broadcasts, or maybe she’ll sell it at a night market for a few fond dollars. He slides it back to her with some cash for the bill. The last of the sun has gone. He missed it. He tries to find the ritual again, like a record needle skipping through to its groove. He ties the strip of cloth across his forehead and drains the last of his beer. The server is showing the 8x10 to the Korean chefs and giggling. He won’t come here next time. Next time, he’ll eat across the street at the deli. Sliced meat on rye. Nobody will know him there. Next time. |